Jani Christou

1926-1970

The function of music is to create soul, by creating conditions for myth,

the root of all soul. Where there is no soul, music creates it. Where there is soul, music sustains it.

Jani Christou –

Chios, 23rd Aug 1968

Who was Jani Christou?

On January 8th 1970, in a car accident a few kilometers outside Athens, the contemporary music world lost one of its most exciting and provocative talents. Although Jani Christou was only 44 when he died, he was regarded by many as one of the leading composers of his generation. He was controversial, highly talented, and greatly admired both in his own country and abroad. And yet although his name remains respected in contemporary music circles to this day, performances of his music are extremely rare.

At the time of Christou’s death, his music was being heard at some of the most prestigious international music festivals in the world, and he was also preparing to unveil the most ambitious project of his career – a large scale contemporary opera based on Aeschylus’s Oresteia (1967-70). However, Christou’s untimely death left many projects incomplete including the Oresteia which would have received its world premiere at the English Bach Festival in London in April 1970, with further performances scheduled for France, Japan, America and Scandinavia.

Jani Christou was born at Heliopolis, N.E. of Cairo on January 9th, 1926, of Greek parents. He was educated at the English School in Alexandria, and began composing at an early age. In 1945 he travelled to England to study formal logic and philosophy at Kingâs College, Cambridge under Ludwig Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell (he attained an MA in philosophy in 1948). At the same time he studied music privately with H. F. Redlich, the distinguished musicologist and pupil of Alban Berg, and in 1949 travelled to Rome to study orchestration with F. Lavagnino. He also travelled widely in Europe, culminating for a short period in Zurich, where he met and attended lectures in psychology with Carl Jung. Christou’s studies in psychology were greatly encouraged by his brother Evanghelos (himself a pupil of Jung) whom Christou considered his spiritual mentor and who exerted a strong influence on his creative thinking. Christou was deeply affected by his brother’s death in 1956 as the result of a car accident, and it was Jani who arranged the posthumous publication of Evanghelos’s book The Logos of the Soul.

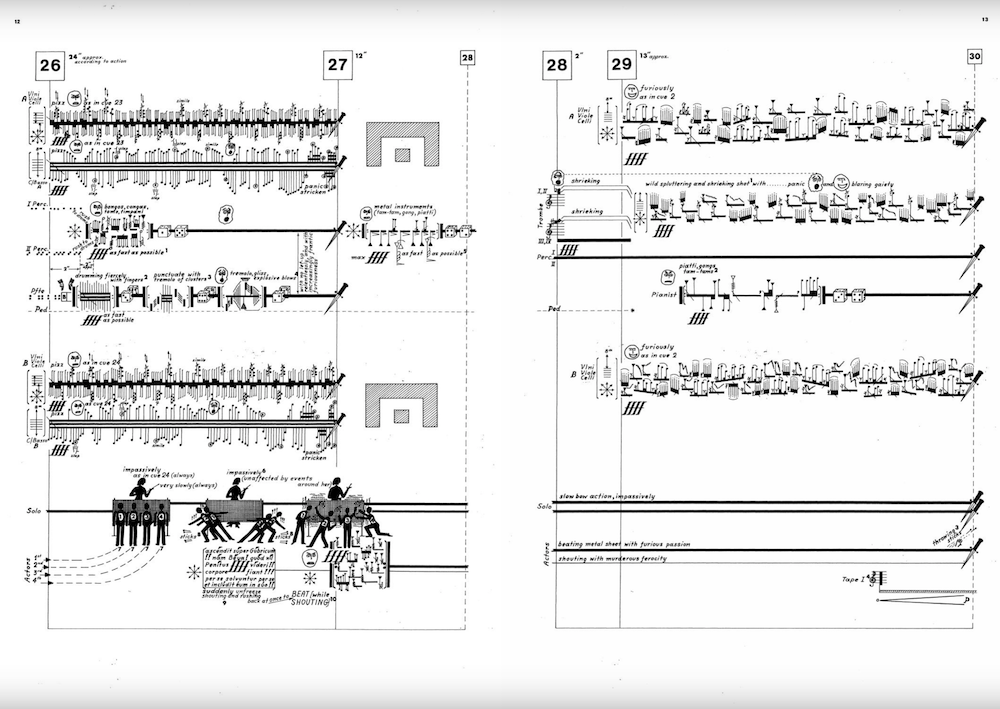

He returned to Alexandria in 1951, and in 1956 he married Theresia Horemi a remarkable young painter from Chios who supported and assisted Christou in all his artistic and creative aspirations. Christou would compose for long hours at a stretch, and when not actually physically engaged in the act of composing would spend a great deal of time studying in his vast library of books and absorbing subjects from philosophy, anthropology, psychology, theology and comparative religions, history and pre-history through to occultism and art. Christou was as much a philosopher and metaphysician as he was a composer, and it is important to understand that all of his music sprang from his philosophical studies and theories. This is particularly so in the music covering the last ten years of his life, where his compositional techniques are at times transmuted beyond conventional music. In a series of 130 Projects (described by John G. Papaioannou as 130 metamusical, ritual works) Christou extends musical syntax to such a degree that the boundaries between music, theatre and everyday ‘life’, merge, coexist and sometimes become mutually independent one from the other: Anaparastasis III (The Pianist) for actor and instrumental ensemble and tapes (1968); Anaparastasis I, for baritone and instrumental ensemble (1968) and Enantiodromia are prime examples of this genre of Christou’s late music.

He returned to Alexandria in 1951, and in 1956 he married Theresia Horemi a remarkable young painter from Chios who supported and assisted Christou in all his artistic and creative aspirations. Christou would compose for long hours at a stretch, and when not actually physically engaged in the act of composing would spend a great deal of time studying in his vast library of books and absorbing subjects from philosophy, anthropology, psychology, theology and comparative religions, history and pre-history through to occultism and art. Christou was as much a philosopher and metaphysician as he was a composer, and it is important to understand that all of his music sprang from his philosophical studies and theories. This is particularly so in the music covering the last ten years of his life, where his compositional techniques are at times transmuted beyond conventional music. In a series of 130 Projects (described by John G. Papaioannou as 130 metamusical, ritual works) Christou extends musical syntax to such a degree that the boundaries between music, theatre and everyday ‘life’, merge, coexist and sometimes become mutually independent one from the other: Anaparastasis III (The Pianist) for actor and instrumental ensemble and tapes (1968); Anaparastasis I, for baritone and instrumental ensemble (1968) and Enantiodromia are prime examples of this genre of Christou’s late music.

The large scale contemporary opera Oresteia, a massive stage ritual based on the text by Aeschylus, for actors, singers, dancers, chorus, orchestra, tape and visual effects (in which several of the Anaparastasis of the fifth period would have certainly been incorporated), would have served as a grand summation of Christou’s life’s work up to that point had the tragic accident on the 8th January 1970 not intervened and cut short the life of one of the musical world’s most unique and highly talented creative spirits. A passage from Anthony Kenny’s book Wittgenstein may provide us with a clue to the philosophy behind his latter works:

What the metaphysician attempts to say cannot be said, but can only be shown. Philosophy, rightly understood, is not a set of theories, but an activity, the clarification of propositions. Above all, philosophy will not provides us with any answer to the problems of life. Propositions show how things are; but how things are in the world is of no importance in relation to anything sublime.

‘It is not how things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists.’

from Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus 6.432, 644 – L. Wittgenstein

Michael Stewart © 1999